THE PARTHENON BLOWS UP DURING THE VENETIAN SIEGE, Sept. 26, 1687.

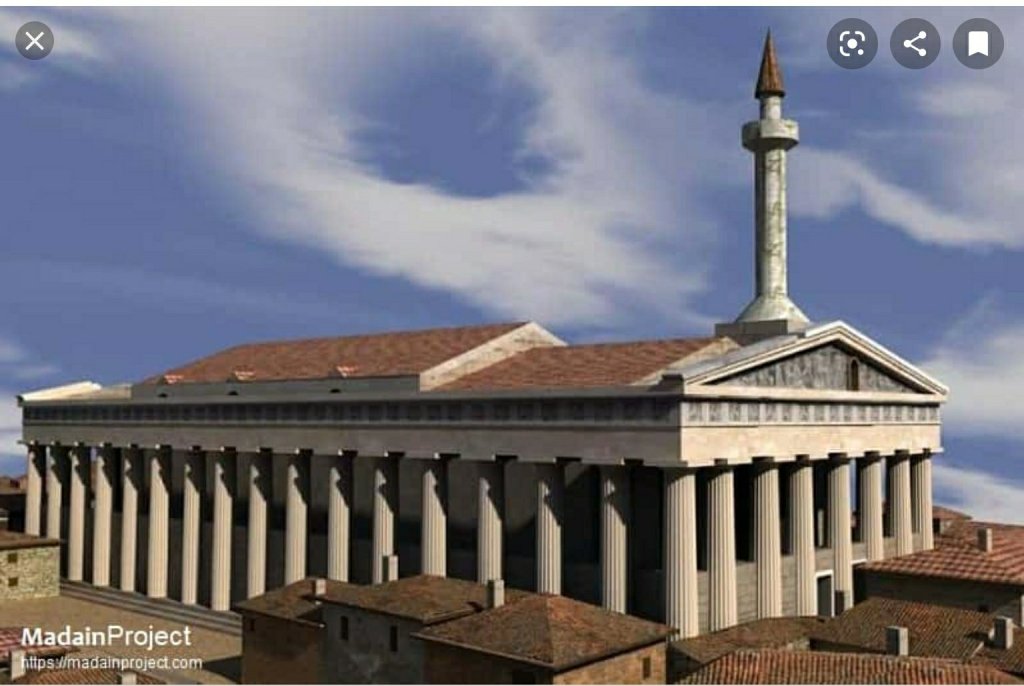

The Parthenon, which was called Temple of Minerva at the time, was almost intact before the arrival of the Venetians.

During the summer of 1687, the Venetian war council decided to send the troops to Athens. The only goal of this expedition was to carry the danger further away into enemy territory, creating a buffer zone between the Turks and the Isthmus of Corinth. It was also intended to ransom the population, demanding the immediate payment of a “war tax”. Not for a moment did Captain General Francesco Morosini intend to keep Athens. The fortress of Athens, the Acropolis, situated nearly 10 km from the shore, was difficult to defend, especially for a maritime force.

The troops, 9,880 infantry and 871 cavalry, were embarked at Corinth on the 20th of September, and the armada set sail that evening, crossing the Saronic Gulf during the night by a favorable wind. The next morning the warships and galleys were able to enter Piraeus without any resistance. The harbor was then called “Porto Lione” or “Porto Draco” because of a beautiful marble lion, three times larger than life, which was situated above the bay.

The Turks all took refuge on the Acropolis as soon as the Venetian fleet appeared, determined to resist as long as possible, counting on the arrival of the serasker. All hopes of any ransom were gone. Morosini immediately gave the order to occupy the town which was not defended by any wall, and the army commanded by Otto Wilhelm von Königsmark marched on two columns.

The troops encamped in the middle of the olive trees, under the celebrated Acropolis, dominated by the imposing Parthenon which, until the autumn of 1687, had withstood the outrages of time. The Acropolis served as a fortress and a dwelling place for the Turks and their families. The Greeks, and the few Latins residing at Athens, were excluded. The latter lodged in the suburbs, on the North and South sides of the hill. The city was, on the whole, quite opulent when compared with other Greeks towns, and its 10,000 inhabitants living in the midst of ancient ruins had a quite comfortable lifestyle, according to various travelers of that time, including Bernard Randolph.

But the Athenians would have their lives suddenly turned upside down. On the 22nd of September, the crews of the galleys were forced to haul the siege artillery until the camp. It consisted of six guns and four mortars. Daniel Dolfin had again been appointed provveditore in campo. The batteries, placed under the command of Count of Antonio San Felice Muttoni, began to operate on the 24th around noon.

According to several sources, Muttoni failed in his task. Colonel Antonio Muazzo states that some of the bombs failed to reach the Acropolis, and fell in the city below, which enraged the Greek population that came to complain to Königsmark. On the evening of September 26, the Swedish general, furious, was going to put “Governor Leandro” (probably Leandro Molvis, the superintendent of the artillery) in command, when a bomb fell directly on the Parthenon inside which the families of the Turks had taken refuge, together with a large stock of munitions. This shot, called “fortunato colpo” by Morosini, had a devastating effect, ravaging the Parthenon and killing 300 people, military and civilians:

« Ne seguì un effetto terribile nella gran furia di foco, polvere, e granate che ivi si trovavano, anzi lo sbaro e rimbombo delle suddette monizioni fece tremare tutte le case del Borgo, quale sembrava una gran città, e mise un gran spavento negli assedianti, restando in questo modo rovinato quel famoso Tempio di Minerva, che tanti secoli e tante guerre non aveano potuto distruggere. »

The fire raged for two whole days, but it was not enough to make the Turks to bend as they continued to hope for relief. It arrived on the 28th at dawn. The troops sent by the serasker were not very numerous: barely 2,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantrymen. As soon as the Count of Königsmark marched against them with the Oltramarini and the cavalry, the small Ottoman army fled without any fight. The garrison had to rely on the generosity of the Venetian Captain General who granted the Turks five days to evacuate the ancient fortress, with the right to carry only their belongings, « che cadauno potrà portare dalla Fortezza alla Marina in un solo viaggio ».

On October 3, 3,000 civilians and 500 soldiers came out and were taken to the harbour where an English ship, two French tartans and three polacres from Ragusa were waiting to take them to Smyrna at their own expense. On the way to Piraeus, some were molested and robbed by unruly soldiers.

Morosini appointed Daniel Dolfin to the position of provveditore of the city of Athens and Count Tomeo Pompei of Verona, commander of the Veneto Reale regiment, governor of the Acropolis. It was necessary to rid the streets of the ruins and the hundreds of corpses on the ground.

The Allies were then able to contemplate at their ease the scattered ancient vestiges which adorned Athens and its environs, as they had already done at Corinth. Many felt speechless, others felt an understandable “ecstasy”. Cristoforo Ivanovich was immensely proud with the idea that the Venetian Captain General had conquered such famous places: « Ebbe il Morosini la gloria di soggettar nello stesso tempo, alla fama del suo temuto nome, e Misistrà, che fù l’antica Sparta, e Atene la Famosa… ».

At the beginning of April 1688, the Venetians finally withdrew from Athens. Many of the Greeks who had sided with them upon their arrival had to move to the Peloponnese to escape the wrath of the Turks who reoccupied the city without a fight.