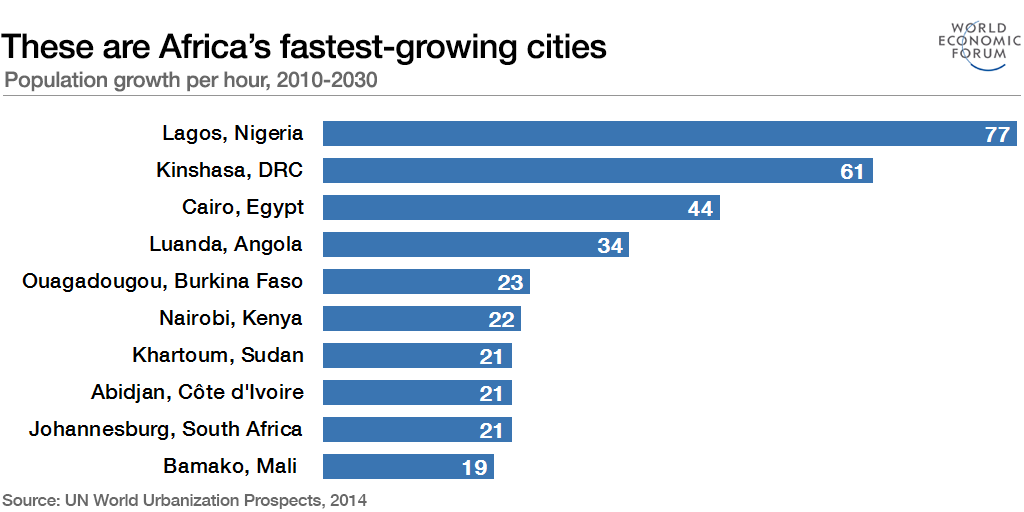

Africans are moving to the city. Already home to the world’s youngest and fastest-growing population, the continent is urbanizing more rapidly than any other part of the planet. Africa’s 1.1 billion citizens will likely double in number by 2050, and more than 80% of that increase will occur in cities, especially slums. The implications of this turbo-charged growth are hard to fathom. Consider how Lagos – already Africa’s largest city – is predicted to expand by an astonishing 77 people every hour between now and 2030.

Africa is not prepared for this urban explosion. By 2025, there will be 100 African cities with more than one million inhabitants, according to McKinsey. That’s twice as many as in Latin America. Runaway urbanization and a growing youth bulge, with most young people lacking meaningful job prospects, is a time bomb. Already some 70% of Africans are under 30. Youngsters account for roughly 20% of the population, 40% of the workforce and 60% of the unemployed.

Africa is suffering from a major urban infrastructure gap. Annual national public spending on infrastructure is exceedingly low: an average of 2% of GDP in 2009-2015, compared to 5.2% in India and 8.8% in China. Not surprisingly, African cities often succumb to fragility. Sixty percent of all urbanites live in over-crowded and under-serviced slums. Around 25-45% walk to work due to lack of affordable transport. With turbo-urbanization, these appalling conditions could easily deteriorate.

Another looming problem is that African cities are set to expand during a period of unprecedented climate stress. Africa’s urban areas are likely to suffer disproportionately from climate change, as the region as a whole is warming up 1.5 times faster than the global average. The strain on basic services and natural resource endowments, as Cape Town’s water crisis shows, is set to increase. If Africa does not find a way to build sustainable cities with greater access to private capital, then they risk becoming both unlivable and indebted.

Make no mistake – Africa’s future is urban. But in the next two decades, African cities will need to do much more, with much less. While national governments will need to step up and implement regulations to raise public finance, African mayors, city residents and businesses cannot afford to wait. A new mindset is urgently required. But this first requires facing up to the scale of the challenge.

Mind the gaps

The urban infrastructure deficits are daunting. Africans need to spend between $130-170 billion annually to meet the continent’s basic infrastructure needs. Yet the region is already facing financing shortfalls of $68-$108 billion. Roughly two thirds of the investments in urban infrastructure needed by 2050 have yet to be made. Complicating matters, a majority of current financing is from the public sector because instability and regulatory confusion deters private capital. Total capital investment in Africa between 1980-2011 averaged just 20% of GDP (as compared to 40% of GDP in the case of East Asia during a period of rapid urbanization). Closing these gaps could increase GDP growth per capita by 2.6% per year.

It is not just the urban infrastructure gap, but the lack of city planning, inefficient land use, regulatory blockages and vested interests that are holding African cities back. The result is sprawling, fragmented and hyper-informal cities. Not surprisingly, African cities are remarkably expensive to live in. According to the World Bank, African cities are 29% more expensive overall than non-African cities with similar income levels. Locals pay a whopping 100% more for transport, 55% more for housing, 42% more for transport and 35% more for food. All of this slows down business, cutting firm productivity by close to half while dramatically increasing the input costs of consumer goods.

Africa’s infrastructure gaps are not by accident. A key reason is that municipal governments are cash-strapped and struggle to generate tax revenue. City authorities often lack the political discretion and financial autonomy to take action. Take the case of Dakar, Senegal, which was prevented by the central authorities from selling municipal bonds to investors back in 2015, resulting in the loss of $40 million of capital. Now compare this to US cities that raised more than $111 billion worth of municipal bonds for infrastructure projects in just two months last year. Cities in Africa raised the equivalent of 1% of this amount over the past 14 years.

The region’s national and municipal leaders have no time to waste. They need to take the right steps to attract private investment for urban infrastructure. Foreign and domestic investors want the same thing: political and economic stability, predictable regulatory environments, stronger property rights, and credible plans and project pipelines. Yet most of these basic preconditions are still in short supply across Africa. Without coordinating agents – be they forward-looking firms, large investors or third-party agents that de-risk investment – cities are unlikely to take off.

Bridge the gaps

The real question is: how will African cities absorb double their population while using just half the resources over the next 20 years? And how can this be done while improving overall quality of life? The good news is that the solutions are potentially closer at hand than many assume. A major part of the answer lies in employing new (and home-grown) technologies, building smarter infrastructure and harnessing the dynamism of the informal sector.

African cities are only just starting to reap the dividends of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Mobile phone penetration is connecting all corners of the continent, and data generated from hundreds of millions of devices and cheap computing power can potentially improve urban living. Technological innovations such as solar photovoltaic systems, battery storage, IoT sensors and even satellites are rapidly falling down the cost curve. To wit, Kenya just became the first sub-Saharan African country to launch a satellite into space.

Despite their many challenges, or perhaps because of them, African cities are dynamic and creative. Most urban services – whether transport, energy, water, waste management, telecoms, housing or public security – are provided by informal private providers. Consider public transit systems: 70-95% of public transit rides in African cities are supplied by informal, independent operators. They provide a vital, albeit sometimes dangerous and costly, service to citizens. Or consider Cambridge Industries in Addis Ababa, which is presiding over Africa’s first waste-to-energy facility. Working with China’s CNEEC and the Ethiopian government, they are supplying 30% of the city’s energy needs from 80% of its rubbish, most of it deposited by local waste collectors.

Urban informality cannot be construed as a problem, but rather an asset and sign of resilience and agility. When exploring innovative financing solutions, the task for city planners and investors is maintaining the virtues of informality (demand responsiveness, job creation and self-sufficiency) while reducing its vices (unsafe conditions, low-quality services, unfair labour practices, and at times inefficiency and high costs for consumers).

Here are four ways that African cities might start bridging the infrastructure gap:

Accelerate investment in technology deployment for smarter urban infrastructure

Many compelling solutions are poised for scale. A shortlist includes Kenya´s Upande, which uses IoT to manage water leakages and delivery; South Africa’s Where is My Transit, which facilitates routing of transit systems across African cities; Nigeria’s Rensource, which provides distributed solar and replaces polluting diesel generators in homes across Lagos; Nairobi’s Taka Taka, which collects 30 tonnes of waste every day and recycles about 90% of it; Uganda´s CSquared, which is laying fibre optic cable across Kampala, Accra and other African cities; and poa! internet, which provides affordable public and home wifi across urban slums in Kenya.

In the US, for example, there are dedicated funds committed to scaling urban technology such as Urban.us and Urban Innovation Fund. There are no equivalent players in Africa. Despite the rapid growth of impact investing in Africa, most funders shy away from companies tackling urban challenges for fear of government interference and higher capital requirements.

Develop comprehensive data analytics to drive smarter decision-making and investments in the future of African cities

The good news is that there are growing reservoirs of structured and unstructured data available from satellites, IoT networks and international and local agencies. But this data is still inaccessible, fragmented and messy. Finding a way to weave this information together could enable more effective and efficient investments, particularly to support the urban poor.

Reframe the debate on urban real estate development across Africa

There are, of course, smart cities popping up across the continent: Eko Atlantic in Nigeria, Tatu City in Kenya and Vision City in Rwanda, to name a few. While offering visions of the future, most of them are failing when it comes to providing affordable and inclusive options for the majority of Africa’s urban residents. Flagship projects that set a new standard for affordability, accountability, economic opportunity and sustainability are required.

Invest in essential cutting-edge research to drive this work forward

The University of Cape Town’s African Centre for Cities (ACC) is a terrific example of how local scholarship is shaping urban planning decisions. Donors such DFIDand the World Bank are already supporting research, but more is needed. If cities are where the future happens first, then Africans need to invest more in their knowledge capital today. An African Urbanization Fellows programme, attracting the best technologists, urban planners and policy-makers, would be a good way to start.

An integrated ecosystem approach can help convert these proposals into action. It is probably time to establish a platform for accelerating urban innovation, a kind of Sidewalk Labs for Africa. While Sidewalk and others are busily reimagining city life in North America, they are not focusing on where tomorrow’s urban explosion is taking place. Africa needs an organization that can help incubate local innovations under one roof – an investment vehicle, a data platform, a real estate group and a research consortium that partners with municipalities to help them reimagine their future.

By 2050, more than 1.3 billion Africans will call a city home. If they are to live with dignity and seize tomorrow’s opportunities, Africa needs to assemble the greatest minds in urban planning, technology and sustainability today.