“The reform of zoning codes is not primarily a technical endeavor. It is a political endeavor. If you want to change it, you have to get your hands dirty in politics, and become adept at the art of political persuasion. You need to live in the real world of electoral politics, and not in the theoretical world of shouting at people on Twitter.”

It’s Time to Get Real About Zoning

By Jason Segedy

July 30, 2020

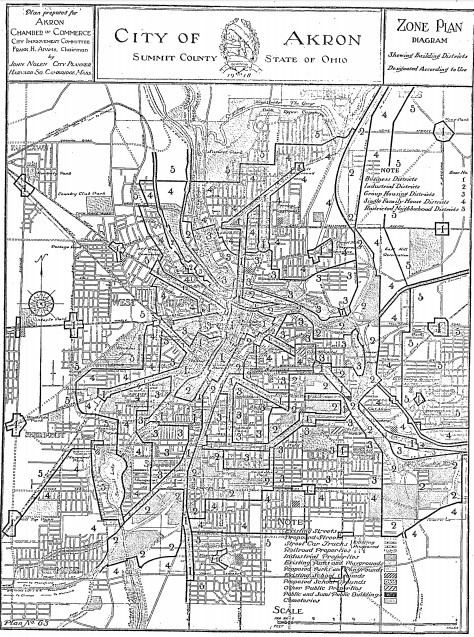

Zoning map prototype, Akron City Plan, 1919

Recently there has been quite a bit of discussion about the need to reform zoning codes in American cities – particularly the portions of those codes which mandate single-family, detached housing as the only permitted land use across large swaths of our cities. The call for reform is increasingly cross-ideological, involving voices from the left, primarily concerned with social justice and economic inequality; and voices from the right, primarily concerned with free markets and private-property rights.

It probably won’t surprise you to know that, as the Planning Director of a mid-sized American city, I have thoughts on this.

I am on board with widespread zoning reform. There is no question that most zoning codes, in most places, should be carefully assessed, reevaluated, and reformed. Some should probably be scrapped altogether and replaced.

I have always believed that a simplistic framing like “Is zoning good or bad?” is unhelpful. This is like asking “Is a hammer good or bad?” It is good if you want to pound a nail. It’s bad if you want to repair a watch. Zoning and land use regulation, in general, are no different. They are tools, and they have their place.

It is important to remember why and how these regulations came about in the first place. Akron’s zoning code, for example, was established in 1922. When it was first adopted by our City Council, we had just grown from a population of 69,000 to 208,000 in one decade. We were one of the most industrialized and polluted cities on the face of the earth. The city smelled like burning rubber continually, as the factories of Goodyear, Firestone, B.F. Goodrich, and General Tire churned out half of the world’s tires, and most of its rubber products, 24-7. The pollution was so bad that black snow fell in the winter, and the soot often needed to be brushed off of the cars of the rubber workers at the end of their shift. The idea that the city should be subdivided into districts where housing and heavy industry would be separated from one another, by force of law, was not a crazy one.

But, as we all know, many of the early 20th century problems that zoning codes were originally written to address are no longer much of a live issue in most places. And like all regulations, there was significant scope creep over time, particularly with regards to restrictions that governed the intensity of residential development. Some of it was done with honorable intentions, as memories of the disease-ridden, crowded and miserable conditions of 19th century industrial slums were still fresh in people’s minds. And, of course, some of it was done with dishonorable intentions, designed to segregate residential neighborhoods by both race and class.

What were seen as fairly innocuous regulations that seemed like a good idea at the time, like mandatory parking minimums, large setbacks, separation of retail and residential uses, and regulations governing the density of housing, are now widely viewed by planners as rules that have simply served to suburbanize our cities and are antithetical to the creation of vibrant urban places.

So, sign me up for widespread zoning code reform. And yet, for all that, I find myself increasingly irritated and dissatisfied with the discourse around this topic, for reasons that I will explain shortly.

Reforming a zoning code is no small task. A few years ago, Buffalo completed one of the largest and most-comprehensive zoning reforms ever undertaken by a major American city. Shortly after the new code was adopted, my zoning manager and I had a conference call with the Buffalo city staff who spearheaded the effort to reform the code. If I recall correctly, they told us that it took something like five years, 255 public meetings, and several million dollars.

There is a lot of chatter on urbanist Twitter and in the national media about zoning. I find much of it unhelpful and uninformed. But more than anything, I find it incredibly frustrating, because it is so damn theoretical.

So let’s get real about zoning for the next few minutes. If we are ever to hope to reform our zoning codes, we need to get out of the realm of theory entirely.

People, primarily on the left, shout that it’s time to abolish single-family zoning, while people on the right shout back that all of this is a nefarious plot to destroy suburban life as we know it. Even President Trump has gotten involved.

So, instead of focusing on practical steps for reforming zoning that could be undertaken at the local level, the whole thing degenerates into this ridiculously theoretical discussion about whether or not the federal government has the power to abolish single-family zoning.

Just as with nearly all of what passes for discourse on public policy these days, it devolves into two groups of ideologues shouting at each other across an unbridgeable chasm – which is one of the primary reasons that our society has ceased to be able to implement meaningful reform of just about anything important.

There is also a lot of idle chatter about zoning that blames urban planners for all of this. The people who want to abolish single-family zoning accuse the planners of being mindless reactionaries who are standing in the way of progress, while people like Stanley Kurtz accuse the planners of being leftists who are working in the service of Agenda 21 and ushering in the New World Order.

Let’s get real once again. Zoning is not primarily, nor is it fundamentally, an urban planning process. It is a legislative process. It has the force of law, and it is ultimately enacted by legislators, not by urban planners. You might be surprised by how little influence many planners have upon land use policy in our cities.

I’ve been an urban planner for 25 years, and I’ve talked to a lot of people who work in my field. The vast majority of today’s urban planners would love to see our zoning codes reformed so that they are less restrictive, particularly with regards to limits on residential development density, minimum parking requirements, and the separation of retail and residential land uses.

When you talk about changing zoning, you are talking about changing law, which means that your primary audience is not urban planners. Your primary audience is city councils, township trustees, and other duly-elected local legislative bodies. These are the people who you need to convince.

Which brings me to my next point. Given this reality, the reform of zoning codes is not primarily a technical endeavor. It is a political endeavor. If you want to change it, you have to get your hands dirty in politics, and become adept at the art of political persuasion. You need to live in the real world of electoral politics, and not in the theoretical world of shouting at people on Twitter.

So, if you want to change the system, it’s not enough to tweet away self-righteously at a bunch of like-minded urbanist followers, to a cascade of likes, about “how much sense” zoning reform makes, or how “irrational” existing codes are, or about “how stupid people are” for not seeing the self-evident truths about zoning that you can see.

This is law. This is politics. If you want to change it, you actually have to convince people. And when I say “people”, I don’t just mean legislators. I mean the general public. Because they vote for the legislators. And those legislators like to get reelected.

None of this is theoretical. The number-one reason that zoning codes don’t get changed, is because the general public supports the zoning and land use status-quo. It is true that there is a growing left-right consensus on the need for zoning reform. But there is also an entrenched left-right consensus on the zoning status-quo.

The dirty little not-so-secret about land use regulation in the United States of America is that most conservatives and most progressives like it just the way that it is. Researchers who have surveyed Americans about their support for development have found no evidence that conservatives oppose regulation or embrace free markets when it comes to housing. Similarly, in other surveys, liberals who say they support social and economic justice also oppose new development near them, and their personal interest as homeowners trumps their ideology on social justice.

I know that this goes against the grain of our particularly dysfunctional political moment, but if you are going to make a credible case for changing the zoning code, it is a really bad idea to tell the people who could help you change it how stupid they are, or how morally bankrupt they are for opposing your proposed reforms.

This isn’t a doctoral dissertation. It’s politics. You are going to need to patiently and coherently explain how the legislative reforms that you are proposing will make life better for your community overall, and you will also need to explain how what you’re proposing will benefit (or at least not harm) most of the people who oppose it.

There are a lot of opportunities to do this. Parking reform is a good example. People get emotional about parking, and always default to wanting more of it. But few people are truly dogmatic about mandated parking minimums, and can be convinced to change their mind if you take the time to make a sound social, economic, and environmental case for why the government shouldn’t be in the business of forcing people to build more parking spaces than they want to.

So, there is some low-hanging fruit out there. As this worthwhile article says, “Ultimately, then, the need for reform should focus on the core parts of zoning ordinances that stubbornly prevent salutary change without an overriding and compelling justification.” I agree. That is a good place to start. There is plenty of work to be done there.

But there are far thornier zoning-related political challenges lurking out there. Zoning codes are local law. And this is one of the toughest things about enacting comprehensive zoning reforms that would lead to more equitable outcomes, and reduce residential segregation along economic and racial lines.

There are a mind-boggling number of local governments in the U.S., especially across the Northeast and Midwest (which, not-coincidentally, happen to be the regions where our most racially and economically segregated metropolitan areas are located). Given this reality, the ability of many suburban governments to use exclusionary zoning regulations (large minimum lot sizes, prohibiting multi-family dwellings) to virtually zone out anyone who is low (or even moderate) income is quite profound.

And yet, most of the discussion of zoning reform focuses on central cities, when the reality is that, in nearly all cases, these places are already the most economically and racially-integrated political units in their respective metropolitan area.

Many housing and transportation problems could be solved, or at least alleviated, if more suburban communities would be willing to allow more apartments, or single-family homes on smaller lots, so that low and moderate income households could be closer to suburban job and shopping opportunities.

Reforming exclusionary zoning in the suburbs would also help reduce concentrated poverty, which mountains of social science research have demonstrated has especially pernicious social and economic effects on low-income households. Being poor in a neighborhood that is not poor leads to far better life outcomes, especially for kids.

But, again, none of this is a technical issue that involves urban planners. It is a political issue that involves legislators. Our widespread patterns of racial segregation and economic inequality at the metropolitan level will not be fixed by tweaking the arcane provisions of the zoning code back in the central city. Suburban communities are the ones that will need to take the hardest look at their zoning codes. Few of them will have any interest whatsoever in doing so.

A lot of would-be reformers focus on the wonkier, more technical aspects of zoning, because that is far easier. But the politics of this is far more critical and difficult, because people are complicated, and they are not ideologically consistent.

Many a rock-ribbed conservative believes in strong and intrusive regulation of [other people’s] private property. And, at the other end of the ideological spectrum, there are countless left-wing attorneys and professors, some of whom have devoted their careers to social justice and the reform of land use regulations, who yet live in economically and racially segregated neighborhoods in suburban communities with highly-restrictive zoning codes.

The right-winger who wants the government to restrict the use of their neighbor’s property, and the left-winger who lives in the segregated neighborhood always have an excuse for why they are the exception.

I am not a purist. I am not here to judge them. I don’t really care if, or why, they are the exception. I am here to illustrate the non-theoretical reality of a complex political issue.

Because, in the end, we don’t have the system of zoning that we do because a bunch of urban planners decided to make it that way back in 1922. We have the system of zoning that we do because most citizens, and the elected leaders who represent them, want it to be that way. If we want to change it, we need to start with them.